As part of

The Last Terminal, Volume III

Part 6: Colonotopia

gerlach en koop exhibit works by Steve Van den Bosch, Annaïk Lou Pitteloud, Shimabuku, Ismaïl Bahri, Gabriel Kuri, Hendl H Mirra, Mark Geffriaud, Ian Kiaer and Jacqueline Mesmaeker

27.03.2025—27.07.2025

Rib

Katendrechtse Lagedijk 490B

3082 GJ Rotterdam

The Netherlands

curator: Maziar Afrassiabi

As soon as the grip of darkness slackens, the boundaries between you and the objects around you lose their fluidity. Gradually they start to distinguish themselves, moving away from you, from the walls, from the floor, the ceiling. And you are moving away from them. Mutual sympathy turns into differentiation: the headphones on the couch with the cord in an elegant curl on the floor; the scissors on the desk, not closed but in the shape of an x; the chair that has not been drawn up; the black-and-white postcard stuck on the wall with Blu Tack; the glass of water without water on the small metal table mobiltecnica torino next to the bed; the shoes side by side close to the leg of the table.

You’re washed ashore. You leave behind a stagnant surf of crumpled bed sheets as your feet touch the floor. You open the bedroom door. No longer asleep, but awake? Not quite.

Was machen Sie um zwei? Ich Schlafe. was an exhibition at the GAK, Gesellschaft für Aktuelle Kunst in Bremen in 2020. Four years later, in Rib, gerlach en koop accepted Maziar Afrassiabi’s invitation to restage—over time—their attempt to approach the elusive phenomenon that is sleep by displaying works by other artists. Works that either corresponded to the disintegration of falling asleep or the reintegration of waking up.

During the night of 8th March Rib was exceptionally open until the next morning. Not an event, not nothing, an exhibit. After this good night’s wake, dawn has finally broken the surface. The last stage in the restaging has arrived. All works on display are associated in different ways to the sometimes strange, sometimes frightful, experience of waking up. Frightful? Sure, we’ve all done it many many times in our life. However, just one oblivious moment is needed, one moment of doubt—do I know how to?—and sleep stays, until you die.

Photography: Lotte Stekelenburg

/

JACQUELINE MESMAEKER

Les Portes Roses (1975) consists of thirty-two watercolours all depicting three pink rectangular shapes, each one slightly larger and paler than the one that came before. A long quote is dispersed over the thirty-two A4 sheets with one word (sometimes two) over each shape,a quote from the first chapter of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. We reproduce the quote here as it was printed in the catalogue raisonné published ten years ago by (SIC).* We were surprised to find a pink paper wristband in our copy when we removed it from the shelf. A paper wristband to an event we apparently didn’t attend, or maybe just one of us did. Which event? Neither of us can remember.

‘There were doors all round the hall, but they were all locked; and when Alice had been all the way down one side and up the other, trying every door, she walked sadly down the middle, wondering how she was ever to get out again.

Suddenly she came upon a little three-legged table, all made of solid glass; there was nothing on it except a tiny golden key, and Alice’s first thought was that it might belong to one of the doors of the hall**; but, alas! either the locks were too large, or the key was too small, but at any rate it would not open*** any of them.**** However, on the second time round, she came upon a low curtain she had not noticed before, and behind it was a little door about fifteen inches high: she tried the little golden key in the lock, and to her great delight it fitted!’*****

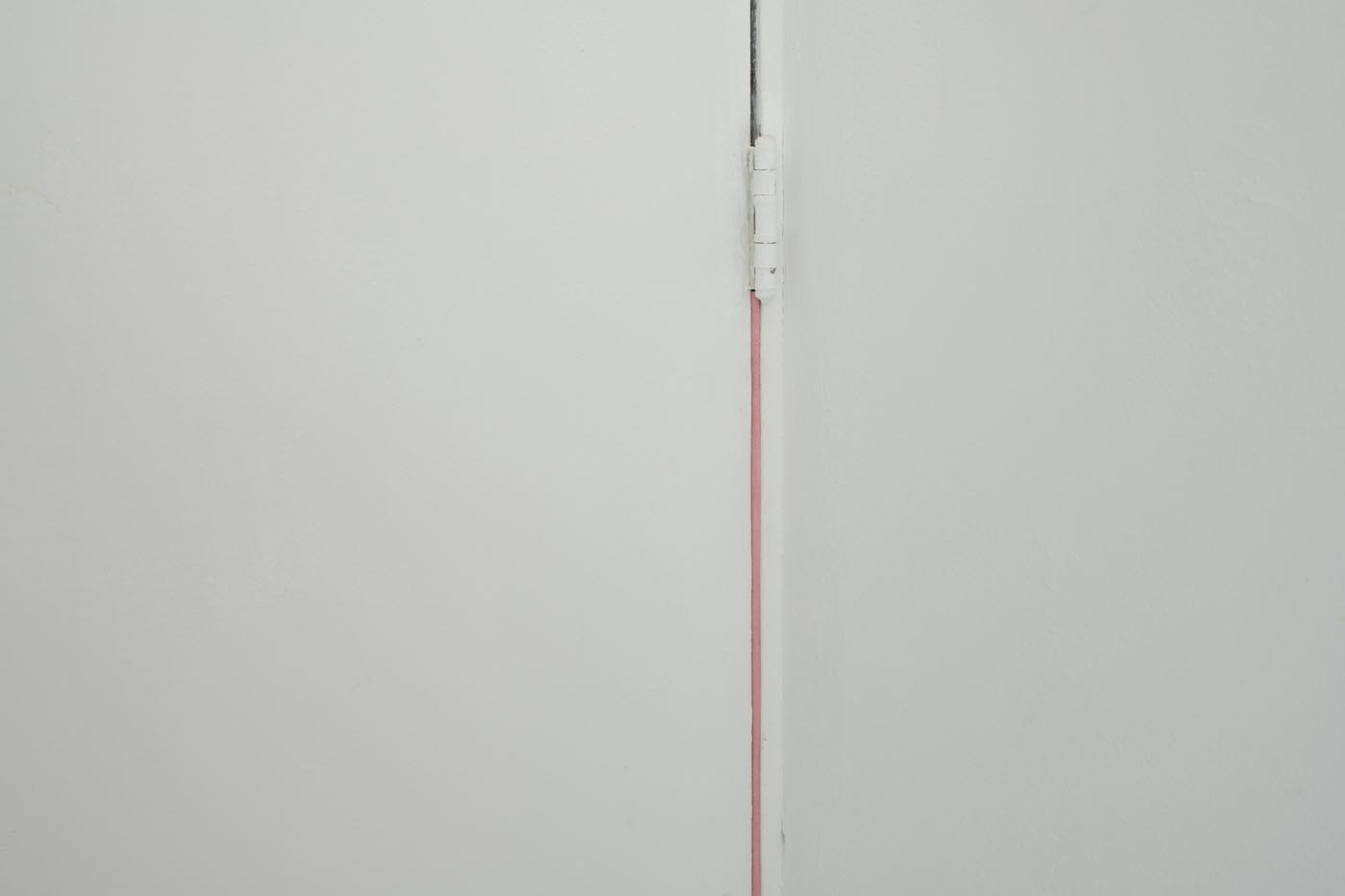

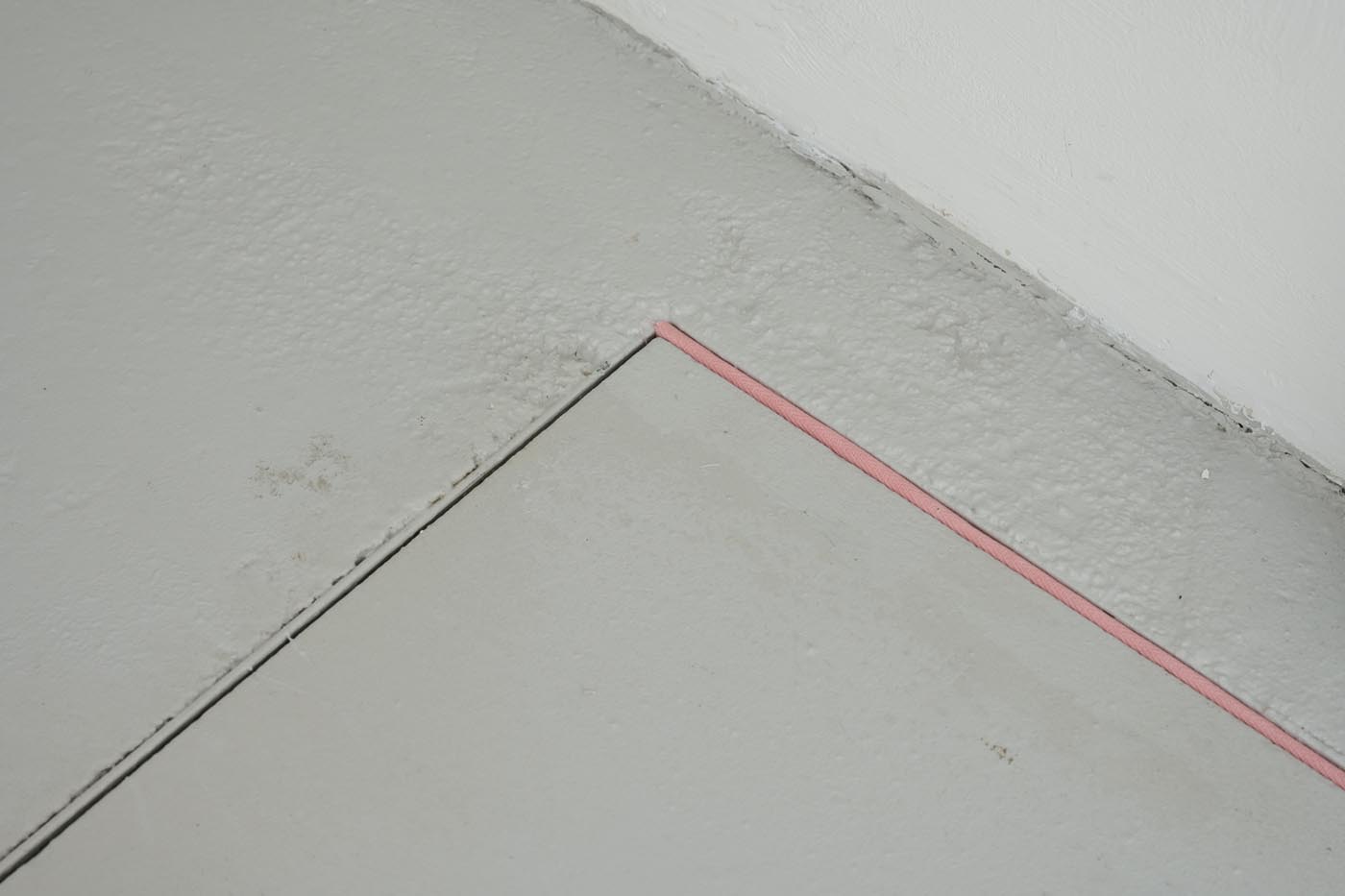

The disappearing doors will not be on display in this exhibition, but its counterpart will: Introductions Roses, the fitting of pieces of pink fabric in certain interstices repérés, found gaps or blind spots in the artist’s home that were photographed and made into a slideshow (1995). Mesmaeker expanded the slideshow

into a site-specific intervention (2019) for the Brussels exhibition space La Verrière, it has been especially adapted for Was machen Sie um zwei? Ich schlafe and will be for Om acht uur? Dan word ik wakker. The pink fabric will direct the gaze to the details of the room, expelling the cloud-like whiteness of sleep and giving way to the brightness of the day. The return of detail.

Yes, of course, Alice’s white rabbit has pink eyes.

* Lewis Carroll, ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’, in: Jacqueline Mesmaeker. Œuvres 1975–2011, ed. Olivier Mignon, Bruxelles: (SIC) – Couper ou pas couper, 2011, p.12.

**Exhibited in BOZAR in 2020, we could see that the door ‘hall’ was already completely colourless.

***You could see in the (SIC) catalogue that the ‘open’ door still contained a trace of pink.

****The thirty-two watercolours end here.

*****Until It Fitted! became the title of a 2007 exhibition at Etablissement d’en face, perhaps as a way to make up for the remaining part of the quote. Les Portes Roses was documented during this exhibition. If the bleaching process continues at the same pace, we will see the ‘little golden key’ disappear in thirteen years time, the ‘solid glass table’ in twenty-six years …

STEVE VAN DEN BOSCH

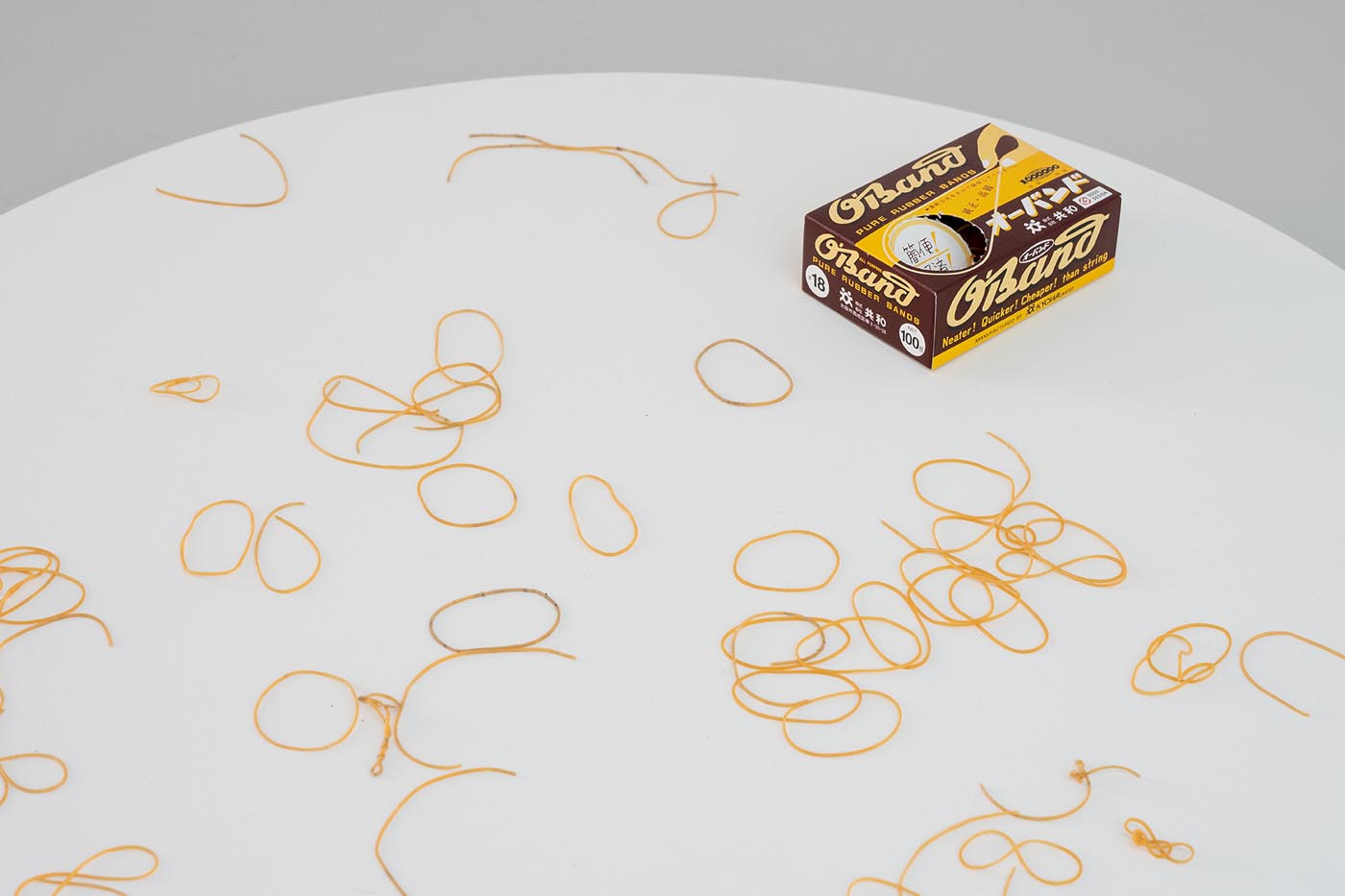

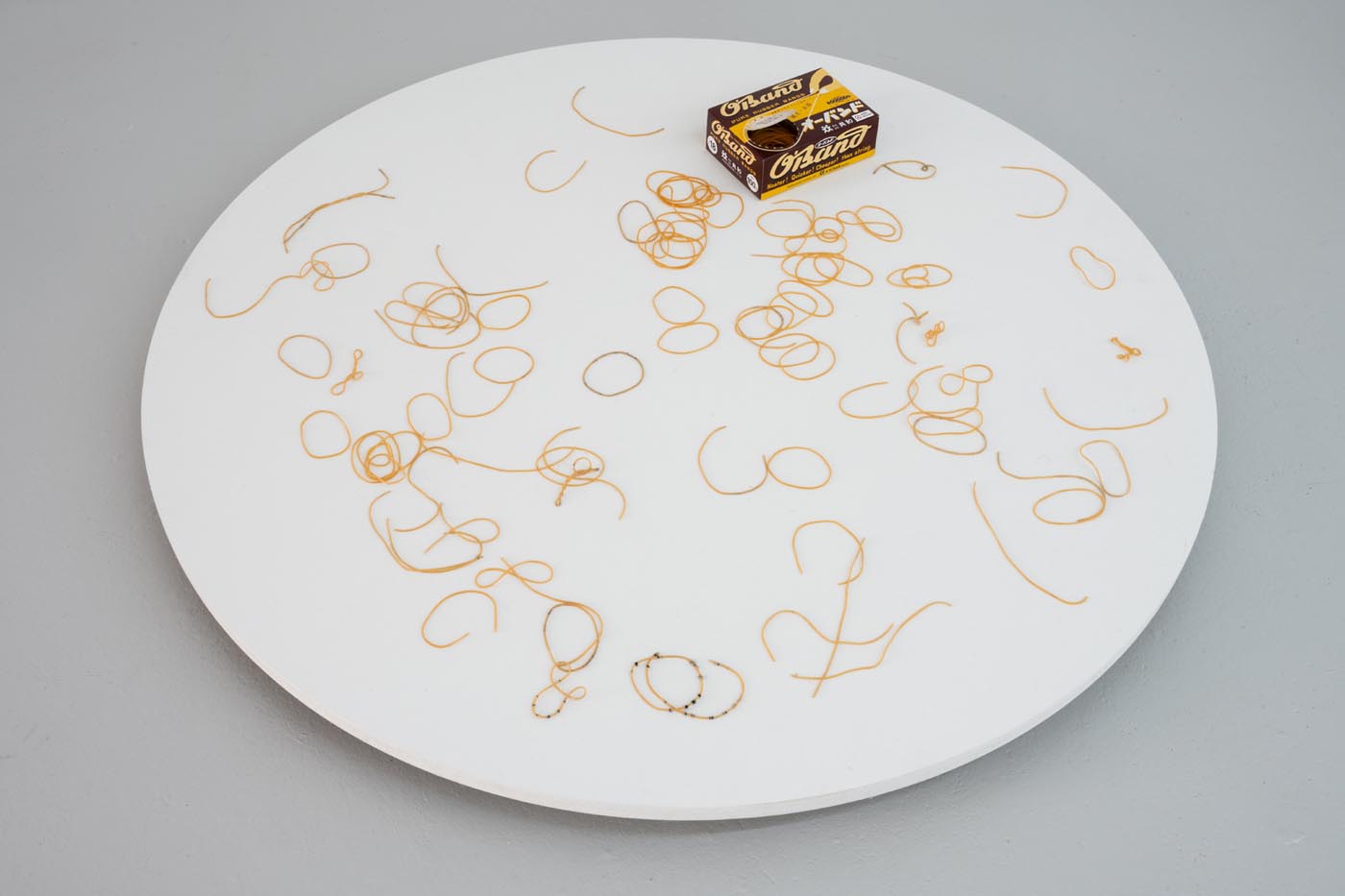

You can’t look for I know, but when you ask me I don’t in the exhibition, but you can find it. Finding it would be the equivalent of being slowed down by it, ever so briefly, when the sole of your shoe sticks to the floor almost unnoticed and then tears itself loose audibly: kgrr.

It’s the same when you tear yourself from sleep, and that is often not quiet either – kgrr, startled by some unfamiliar sound that a part of your dormant brain, a part that is deeply hidden but still vigilant, registers.

You remember how suddenly the lights come on in a club, after the music has stopped and the silence, almost tangible, is only broken by these sounds of shoe soles sticking to the dance floor: kgrr, kgrr, kgrr. A wake-up call, a disenchantment.

One thing is missing here in the classic triangle between you – the visitor – the architectural space, and the object. Between the mounting glue and the visitor there is nothing, until saturation slowly turns it into an image to be seen. Subsequent visitors will eventually exhaust the work until it becomes its own documentation. Just an image, a documentary image. No adhesive strength left, no more sound to be heard. One would be tempted to think that the work is gone.

Wide awake.

ISMAÏL BAHRI

Somebody showing you something. What these things are – not things but fragments of things – you can’t really discern. The wind makes it difficult to see more than a fragment when the hand opens. You see a fragment of a fragment. You are tempted to consider it as one, single thing. Maybe it is. A single thing that changes shape, colour, texture while you’re looking at it. It changes because you’re looking at it.

An earlier version of the video is titled Lâchers [Releases]. A hand releasing again and again. Leaving it to the wind. But it’s an ongoing project; whenever the wind is good, Bahri returns to add new material. This version is titled Saisir, a French verb that means ‘to grab’, also in the sense of ‘to grasp’, ‘to understand’. The best English translation would be: Seize. And yet that would be just the opposite: a hand that tries to hold on to something. Keeping it from the wind, so that it doesn’t blow away.

Looking at it means that you’re trying to hold on, too – to remember what you just saw.

‘Repetition’,* says François Piron, ‘is an instrument of insistence’. ‘Repetition is a way of getting everything out of yourself and out of things in order to retain the tiny amount that resists’, Ismaïl Bahri answers. ‘I try to get to the point where it holds together, but in the hope that, from that point, having persisted, something continues to escape, a vulnerability that is expressed through tremors or vibrations.’

After many attempts, you finally wake up.

*This and subsequent quotes appear in: ‘Leaving It to the Wind’, a conversation between Ismaïl Bahri, Guillaume Désanges, and François Piron, in: Instruments, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2017, p.158.

ANNAÏK LOU PITTELOUD

An Executive Series Ford Lincoln Town Car was found in the port of Antwerp. Koffie Natie, a coffee import-export company, found it submerged in its basin during a shipping manoeuvre, extracted and stored in its car park where it remained for many years. The car was probably new when it was sunk in the harbour, as evi- denced by its perfectly preserved blue leather interior, while its bodywork bears the traces of its immersion.

The car was exhibited under the title They on the grounds of the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten in Amsterdam during the open days of 2010. As it was impossible to sell or store this piece, the car was sold to a shady figure after the exhibition and may now be driving through the streets of Amsterdam.

The short film Perfect Europe (They) was shot when the car was discovered, on the evening before it was removed from the port of Antwerp. Thus one piece bears witness to another, of which nothing remains.

MARK GEFFRIAUD

Every time you pass through a doorway, your thoughts are somehow reset. Most of what you had in mind is erased to make room, to adapt to the new space that you are entering. Though we usually don’t even notice, it does happen that a person enters a room and then suddenly finds themselves unable to remember what they wanted to do there, or what they went there looking for. Scientists call it the ‘doorway effect’. It is a feeling akin to waking up.

A door spindle – being the only element connecting both sides of a door – measures the distance between these two states of mind, making room for a whole new way of looking at this very simple piece of metal.

Measure it and several striking coincidences emerge. The distance range between the holes made to allow knobs to fit doors of different thicknesses are exactly the same as the distance range between the two eye pupils of a human adult, which is to say between 5.5 and 7cm. The holes themselves measure 0.2cm, which is the maximum contraction of a pupil, and the piece of metal itself has a thickness of 0.8cm, which is the maximum dilation of a pupil.

In fact, this object marks a whole set of coincidences. It is a hyphen – a hyphen between different spaces, different territories, different states of being.

And remember, kings don’t touch doors.

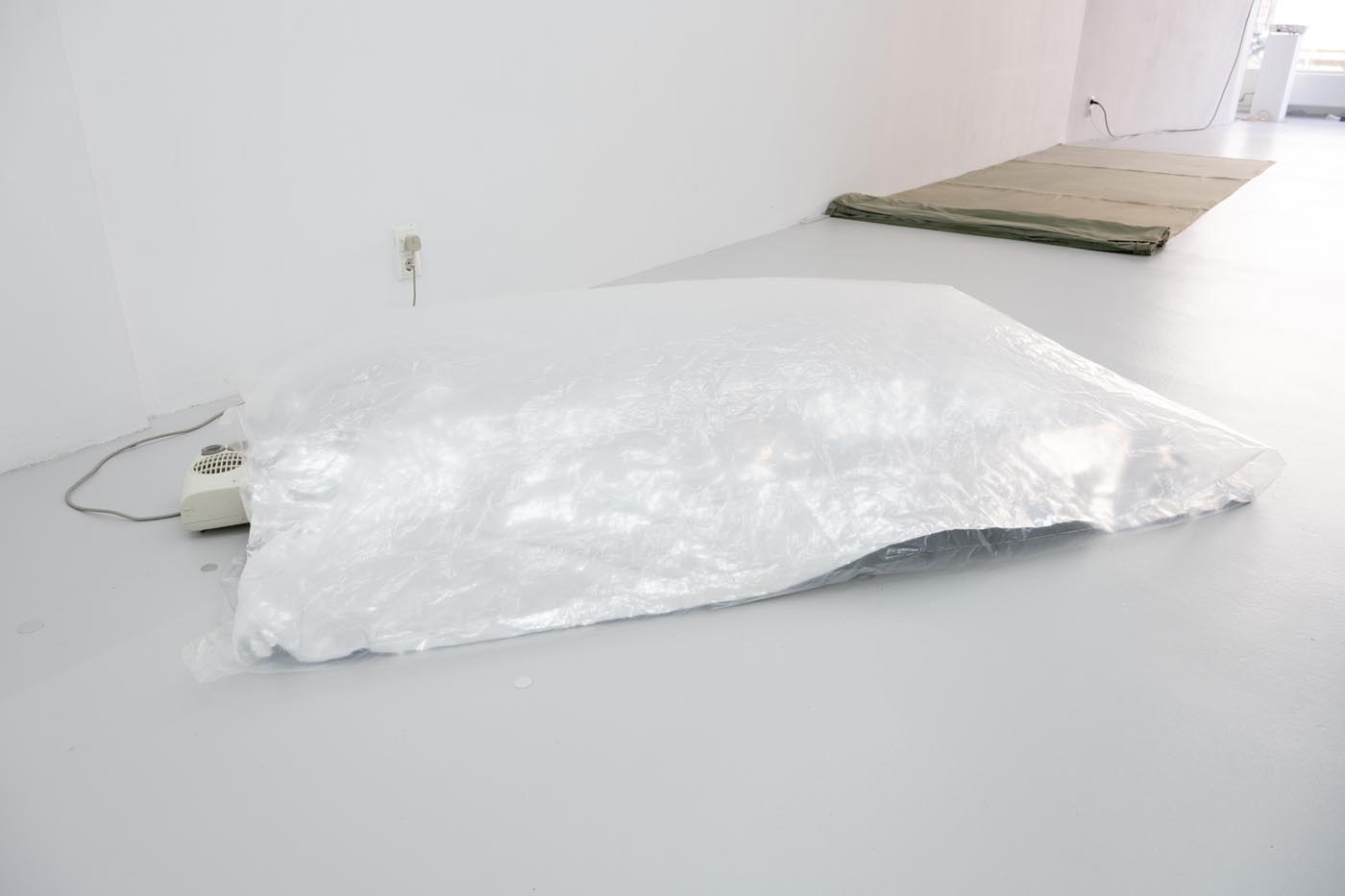

HENDL H MIRRA

Pathetic coverlet for concrete. Made of rectangles of typical American sidewalk size, connected with a slightly darker, fuzzy-mossy stripe. The sculpture can be installed at full length, or with some part of the length accordion-folded at one end only. The fabric was dyed green in sections at a laundromat on the corner of Division and Paulina in Chicago, where Mirra lived at the time. The rectangles were thus in slightly different shades of the same hue, and have since become further varied by inconstant sun-bleaching.

SHIMABUKU

Trying to Wake Up

The night leaves me cadaverous.

The corpse has to be revived. However, I don’t have the impression of being a dead body in the morning.

If someone could see me at that time in accordance with my impressions, I would appear as a sea of clouds, a globulous sea of masses of flakes, a huge object that no doubt borders on the stratosphere.

Cloud though I may be, I am well aware that this state has its enemies, that I will soon have to become active again, de nite, reduced in size … and that it would be wise to start moving in that direction (if it isn’t too late for me to wake up, ever). I get busy immediately.

[…]

Courage! In this mass a will remains.

This headstrongness without a body is vaguely growing.

[…]

Soon I’ll be able to get up. I am now just a few minutes away, and with no obstacles on the road to the near future, I am now a man like minutes away, and with no obstacles on the road to the near future, I am now a man like any other.

It happens, but much more rarely, that I awake (from this half-sleep I’ve been talking about) on four legs. In that case I need more time to return to biped shape, because – I think – of a certain propensity I have for living in that state, which I don’t have for my cloud shape. I’d certainly be prevented from doing so even if I wanted to, and I would be too afraid to stay that way. Although, after all… I’ve come out of it many times in the course of my life. But all it takes is once, when you forget how to deal with it and you stay that way forever, until you die.

[…]

—Henri Michaux, ‘Trying to Wake Up’ [Arriver à se réveiller, 1950], translated from French by David Ball, in:

Darkness Moves, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997, pp.95–100.

IAN KIAER

Cylindrical House Studio, 1929

The distinctive shape of Konstantin Melnikov’s two conjoined cylinders and strange hexagonal windows speak of a structure beyond everyday dwelling. lts geometry, white surface, and remote, singular poise appear designed to provoke rumour of more complex workings within, as if the circular solution and eclipsing diameters might conform to some mystical planetary alignment or map an over- lapping design of halos for an icon of orthodox saints. There can be few buildings with this many windows, over sixty in all, that remain so insistently insular. lt may even be the quantity that works to deny any notion of view and emphasises their alternative function as luminaries. They absorb light from outside but hardly provide an inward glimpse in return. There can be no looking in.

lt is somehow appropriate that their origin can be traced to a fortification sur- rounding Moscow’s ancient Belgorod district, as they a ect to alienate and repel the world.

It’s not only the windows’ honey-comb shape that might prompt the idea of bees, but the way in which its smooth exterior wall, if sliced open, would reveal a complex of interlocking work and living spaces where the incubation of thought and sleep meet. The architect wanted to integrate sleeping and working, dwelling, and thinking throughout his building; hence living-room, studio, and bedroom alternate and dissect like a layered Venn diagram. It is said of the cylindrical motif that he had the Russian hearth in mind* – the hearth as core of the house with the notion of warmth enclosed, its most interior part. To conceive this notion of hearth/heart is to turn the whole building inwards. To think of Melnikov’s building is to think from its inside.

In the house, work and sleep are curiously connected. The circular bedroom is directly below the circular studio. The walls are painted warm yellow; the beds are stone slabs that rise up from the floor like altars, rendering sleep an almost sacred inactivity. For Melnikov, sleep was an area of intense study.** He wrote about a lifetime of sleep, twenty years of lying down without consciousness, without guidance as one journeys into the sphere of mysterious worlds to touch unexplored depths of

the sources of curative sacraments, and perhaps of miracles.***

Here sleep becomes a means of passing from one world to another, mysterious and indeterminate, a place for work’s reserve to be restored and nourished. However, such spaces have a way of shifting tone, from sleep’s place to death’s space. From the thirties on, sleep’s curative sacraments turned to restless slumber as Stalin’s censure became the architect’s incubus, frustrating any possibility for practice. ln such light the warm glow darkens into night, and those concrete beds come ever closer to mortuary slabs. Without recourse to sleep Melnikov turned to dreaming, closing inwards to past projects and painting pictures.

The beginning of those concrete beds perhaps lay in the commission the architect received to design Lenin’s glass sarcophagus. ln this, his first built structure, he had to provide a plinth of sleep for a cadaver forever

preserved, a place of pilgrimage and peering – a windowed tomb. There is something determinedly circular in how this first work, which signals his professional birth, presents itself as a death work. As if somehow opportunity demanded he earn through experience what he had conceived through commission. He could not know that his cylindrical house studio – designed with such optimism as an ideal space for living and work – would eventually become a place for sleep, a house for a corpse.

—lan Kiaer, ‘Cylindrical House Studio, 1929’, in: Picpus, issue 4, Autumn 2010.

*A.A. Strigalev, ‘The Cylindrical House-Studio of 1922’, in: Konstantin Melnikov and the Construction of Moscow, eds. Mario Foss and Maurizio Meriggi, Milan: Skira editore, 2000, p.90.

**ln 1929, Melnikov designed a ‘Laboratory of Sleep’ for workers in the ‘Green City’, see: S. Frederick Starr, Melnikov: Solo Architect in a Mass Society, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978, p.179.

***Ibid., p. 177.

GABRIEL KURI

From the dimensionless void that is sleep ‘we are thrown into the body, into the world, into time’,*

Peter Schwenger writes in his book on the threshold between sleep and wakefulness, and this inevitable and disastrous setback repeats itself every morning. ‘It is our fated placement in the world – fated because we do not choose this place, which is not like any other because it is us.’

We’re washed ashore. We leave behind wrinkled sheets resembling a coastal landscape of frozen waves as our feet hit the floor and we open the bedroom door. No longer asleep, but awake? Not quite yet. It takes us a while and sometimes a while longer to shake off that subtle smell, that hint of melancholy coming from within.

Mourning for a loss will pass, or can pass. We can expect the intensity of the feeling to fade at some point, but this melancholy of waking stays with us, forever on repeat, every morning anew. And precisely because we do not know what we’re grieving for, or even identifying it as a loss, we cannot learn to understand and accept it.

*All quotes from Peter Schwenger, At the Borders of Sleep, on Liminal Literature, University of Minnesota Press, 2012